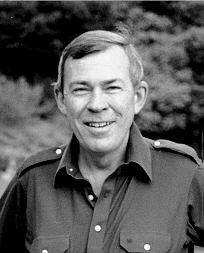

Robert Wohl

Biography

We are sad to announce that Robert Wohl died June 3, 2021.

The following tribute is from Lauro Martines.

I offer these words about Robert Wohl with a divided heart. There is a measure of enjoyment in representing him to younger colleagues, but I also mourn his death. He had long been my dearest friend in the United States.

Although Robert — he never liked the nickname “Bob” – was born in Montana, there was nothing “mountainy” about him. In college at Dartmouth and then at UCLA, his eyes and spirit quickly turned to European civilization, and there they remained. Graduate study took him to Harvard (1959-1960), to the Ėcole des Sciences Politiques (1960-1961), and then to Princeton University, where he obtained his doctorate in 1963.

His first book, French Communism in the Making, 1914-1924 (Stanford, 1966), came out of his doctoral dissertation and took on a bitterly contested decade in the early history of the French Communist Party. Turncoats and loyalists fought over claims concerning the Party’s nature, aims, and actions. Robert’s book provided a more detached and balanced picture, but it moved along customary research rails.

His next book was based on nearly a dozen years of research, as he reached out inquiringly in a quest for his own kind of history. We had endless conversations about this, especially after he had fully envisaged that book, The Generation of 1914 (Harvard, 1979). Now he had hit his stride. Drawing away from narrow specialization of the sort that can blind one, he had elected to write about culture broadly conceived and often verging on so-called “high” culture. In this take, as he saw it, the primary task was to turn to every kind of valid historical source: memoirs, letters, poetry, fiction, treatises, the press, art, manifestos, the cinema, and of course official government documents. Having decided to navigate through this “embarrassment of riches,” he passed to the decisive action: namely, to pull all his findings together into an argument, themes, a thesis. This task quite evidently called for a plenitude of historical imagination. Robert had this in spades.

In The Generation of 1914, moving from a widely held notion claiming that generations issue in cohorts with similar views among the members, Robert found that this was nonsense. Seen as the determining agent, battlefield experience in the Great War did not lead men into holding similar attitudes and views. The members of that supposed cohort took easily to rabidly conflicting political ideas and social attitudes.

There followed, in due course, Robert’s books on aviation, where he again draws on every kind of source. I refer to A Passion for Wings: Aviation and the Western Imagination, 1908-1918 (Yale, 1994)), as well as to The Spectacle of Flight and the Western Imagination, 1920-1950 (Yale, 2005). He had planned to issue a third volume on the subject, bringing the tale up to the present, but “nature” – poor health – got in the way.

The aviation books track the ways in which airplanes and the phenomenon of flight were transmogrified into metaphor, myth, prowess, propaganda, and glory. Among many other matters, including Hollywood’s glorification of airplane flight, Robert highlights the play of elitism in the culture of aviation, such as in Mussolini’s assertion that flying was not for the masses.

In The Generation of 1914, as in his books on aviation, Robert employs the method of collective biography to carry much of the weight of his arguments. The underlying assumption of the method is all but self-evident: when taken and studied in its wider historical context, the individual voice turns into a social voice.

Robert was a splendid colleague, cooperative, hugely committed to the Department, always pleasant, and almost – I want to say — too civilized at times to correct colleagues who called him “Bob”.